Among all the contemplative practices derived from ancient Stoic philosophy, the View From Above stands as one of my favorites. It’s an imaginative way to take a step back, adopt a cosmic perspective, and consider your place in the grand scheme of things—and see how minuscule all your problems and desires and ambitions appear in the vast sweep of time and space.

The French academic Pierre Hadot gave this exercise its name in The Inner Citadel, his excellent 1990s study of Marcus Aurelius and the Meditations, and Marcus leans on this method quite often in his notes to himself. It’s not a technique exclusive to the Stoics; as modern Stoic expositor Donald Robertson notes, it’s found in a variety of ancient Greek and Roman philosophical traditions. Marcus himself mentions Plato and the Pythagoreans in this context, and Robertson argues that the exercise has its origins in the ancient Athenian acropolis overlooking the agora market and all its hectic activity.

Today, we can take our imaginations even further thanks to the views and wonders revealed by modern science and technology—and space exploration in particular. The famous “Earthrise” photo taken by the late astronaut Bill Anders on the Apollo 8 mission in 1968 offers just one example, and the spectacular images of auroras, cities at night, and the like regularly beamed down from the International Space Station provide many, many more. But Carl Sagan’s “Pale Blue Dot,” a photo of Earth taken from Voyager 1 as it hurtled out of the solar system, represents the ultimate View From Above—at least for now.

To put it another way, those of us alive today are able to take a perspective on our own place in the cosmos that ancient philosophers like Marcus Aurelius could have only dreamt about, one that would have seemed fantastical to even the brightest astronomers and physicists just a century ago.

In that spirit, I offer the illustrated View From Above script I’ve written and used myself—though perhaps not as often as I’d like.

Start from wherever you happen to be at the moment. Imagine you’re on a mountain top or tall building, like a skyscraper or the Washington Monument, or an airplane flying at low altitude. You can make out the buildings and streets, the traffic and trees and the like with ease.

Then imagine you’re in an airplane flying at a higher altitude. You can make out large geographic features like lakes and rivers and mountains and glaciers, as well as the sinews of civilization: cities, highways, and the like. If it’s night, you can see the lights of cities glowing in the darkness.

Next, imagine you’re in orbit on board the International Space Station or the space shuttle. You can see the curvature of the Earth, the oceans and the continents in green and blue and brown, the aurorae dancing colorfully in the atmosphere, the nighttime lights of big urban areas. You can also see the stars with exceptional clarity, and on occasion you’re able to spy a glimpse of the Milky Way.

Head out to the Moon, retracing the journeys of the Apollo astronauts. Picture the image of the Earth hanging in space, as in the Earthrise and Blue Marble photographs. Imagine looking at the Earth from the surface of the Moon, or even going beyond the Moon itself to see it and the Earth in a single view as on the Artemis I mission. That’s our home.

Pull back out even further to Mars, remembering the images taken by the orbiters and rovers that show Earth as a bright blue star in the Martian sky. The Moon remains distinguishable even at this distance as you move on to the outer planets, passing through the asteroid belt and past Jupiter.

At Saturn, the Earth remains bright and blue—but it’s now a point of light more than anything else. That becomes even more apparent as you pass beyond Uranus and Neptune to look back billions of miles and glimpse the Pale Blue Dot first captured by Voyager I all those decades ago: as far as you can see, Earth is just a mote in a sunbeam from here.

Keep heading out into the universe, out of the solar system and further into the Milky Way galaxy. The sun itself becomes little more than a point of light in the cosmos, and you begin to encounter the nebulae and other interstellar phenomena that are both beautiful in their own right and remind you of the vastness of time as well as space, of stars being born and dying.

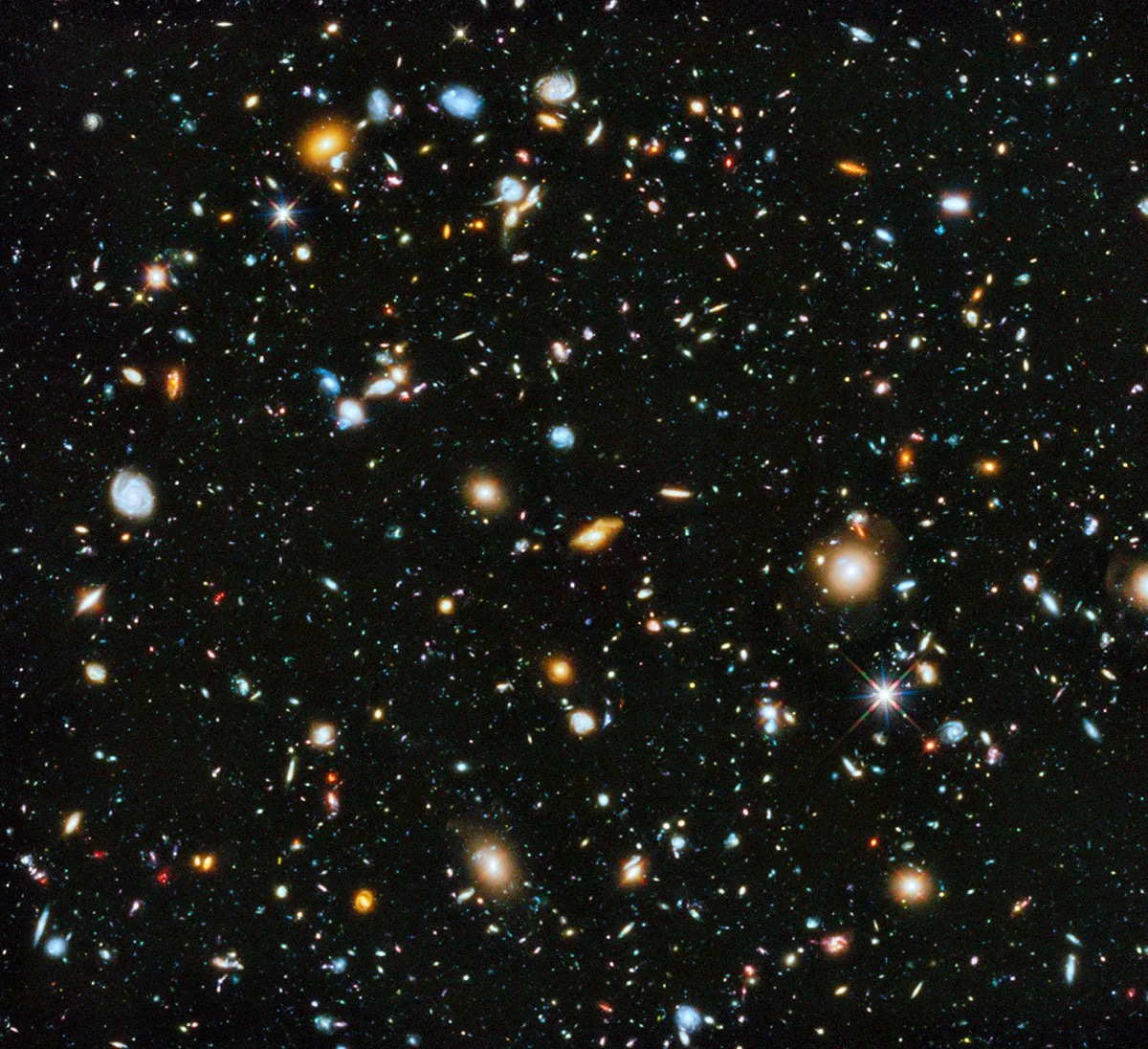

You leave the Milky Way itself behind now, looking back on its spiral arms and bright core. It’s another example of the beauty and structure found in nature, even on a grand cosmic scale. Watch as billions and billions of other galaxies fly past—the universe is so large it’s hard to comprehend it all. There’s so much we don’t yet know about it, including how it will eventually end.

It's time to return back to ourselves. Retrace your journey, heading back through the Milky Way and the solar system back to Earth and wherever it is you happen to be, refreshed and with a renewed appreciation for life that can only be derived from taking the cosmic perspective.

Really enjoyed this, great piece and terrific pictures!