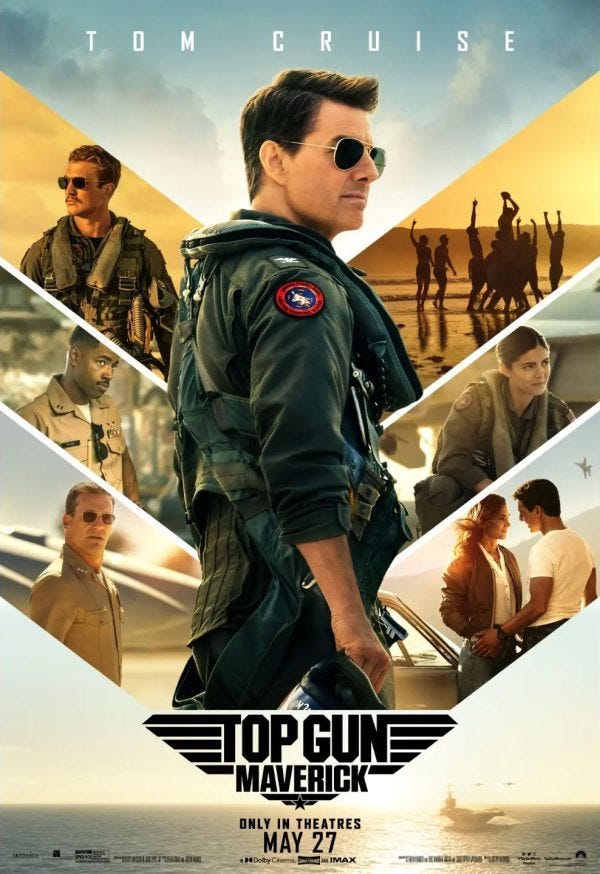

The Need for Speed, Part II

A review of "Top Gun: Maverick"

Top Gun: Maverick wasn’t a movie that needed to be made.

At first glance, it sits comfortably within a recent string of revivals and resurrections of decades-old narratives and characters that’s given us mostly mediocre-to-awful films like Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and The Matrix Resurrections. Even worse, the recent rash of revisitations has made failures out of erstwhile heroes like Luke Skywalker and Jean-Luc Picard in the Star Wars sequels and the Star Trek: Picard television series. Indeed, Top Gun: Maverick director Joseph Kosinski himself helmed a visually striking but otherwise undistinguished Tron reboot way back in 2010.

That makes it something of a miracle that Top Gun: Maverick works so well in so many ways, even if it doesn’t soar to the heights of its iconic 1986 predecessor and falls just short of reaching its full cinematic potential. It’s a thrilling aerial adventure that’s well-executed in nearly every respect, though with a central plot that’s as absurd as it is immaterial to the film itself. This latter-day sequel also offers a solid template to almost certain attempts to bring decades-old characters and stories back to life, one that relies less on idle nostalgia or ill-conceived impulses to defenestrate revered heroes and more on bringing them forward in time while reminding audiences why they found these characters compelling in the first place.

That’s something Top Gun: Maverick does exceptionally well. Though star Tom Cruise has obviously had work done over the years, the movie doesn’t shy away from or make glib jokes about Maverick’s advancing age or the coming end of his career as a fighter pilot. Maverick hasn’t become a failure sulking away in self-imposed exile; as the movie makes clear early on, hasn’t been promoted into management or forced to retire from the only thing he really knows how to do – and do well. But he’s also just about outlived his usefulness, and both he and the Navy recognize that he wouldn’t be a good fit for the upper echelons of military bureaucracy.

It's a point that’s raised often enough throughout the film to become its main (though not only) theme, and one that’s made most explicit when Maverick has an unguarded, emotional conversation with former rival Iceman midway through the movie. Now a high-ranking admiral, Iceman brought Maverick back in to train a new generation of pilots to carry out an exceedingly dangerous and risky mission. But as Maverick notes, he’s first, foremost, and only a fighter pilot – not a teacher or anything else the Navy might expect or want him to be. It’s a scene made all the more poignant by the fact that Iceman, like actor Val Kilmer, suffers from esophageal cancer and strains to communicate with his friend and comrade.

Here, Top Gun: Maverick hits on an important reality of the modern world: the irresistible tendency of organizations to shunt people into bureaucratic and management positions regardless of their actual aptitudes or skills – or discard them when they see them as no longer useful. A position in management becomes the pinnacle of a person’s career, the ultimate goal that any professional should want to strive for – and an indication that something’s wrong with them if they don’t. Though their talents and predispositions may not make a management slot desirable or even suitable for certain individuals, they’re forced to fill out expense reports, supervise subordinates, and the like rather than do what they’re good at. All professional roads, it seems, lead inexorably and inevitably to management. It’s not hard to sympathize with Maverick and his existential quandary given how prevalent it tends to be in reality.

The trouble for Top Gun: Maverick is that while it raises this issue and rightly makes it a central theme, it never really quite resolves it. Given the ways he butted heads with his superior officers over the course of the film, it’s safe to assume that Maverick left the Navy after successfully completing one last and exceptionally perilous mission. But it’s not entirely clear that this is the case as we watch Maverick and his girlfriend Penny Benjamin (played by Jennifer Connelly, and a nice callback to a line from the first film) fly off into the sunset in the P-51 Mustang fighter he’s lovingly restored. Is there life after the Navy for Maverick? Perhaps, but the movie ends with enough ambiguity to leave it an open question.

Much the same could be said for the other themes and conflicts the movie raises and otherwise handles quite well. Maverick’s clash with Rooster (a well-cast Miles Teller), the son of his late backseater and friend Goose from the first film, is resolved by the end of the movie but could have been put into sharper relief – and thereby had an even stronger emotional impact – earlier on. It’s left to audiences to assume that Rooster resents Maverick over his father’s death for a good deal of the movie, but roughly halfway through we’re informed that Rooster harbors a grudge against Maverick mainly (though not exclusively) for keeping him out of the Naval Academy and holding back his career.

Nor is the competition between the young pilots Maverick instructs anywhere near as fierce as in the 1986 original. This question mainly relates to the film’s basic story structure: our protagonist doesn’t participate in the contest himself, but instead supervises and judges it. Nor do Maverick’s brood of young fighter pilots face off against one another as directly as Maverick and Iceman did back in the day. Where the original movie embraced long-standing romantic notions of fighter pilots as larger-than-life knights of the sky, moreover, Top Gun: Maverick offers a more down-to-earth – in more ways than one – take on military aviation as an essentially cooperative endeavor. The young naval aviators we meet this movie still have much larger egos than other pilots, but they’re no longer writing checks their bodies can’t cash.

Whatever its shortcomings on these fronts, however, Top Gun: Maverick handles these themes and problems well enough to work surprisingly well in its own right. It manages to harness audiences’ affection for the original movie without lazily indulging in nostalgia to carry it through; to steal a phrase from George Lucas, “It’s like poetry, they rhyme.” The opening scene of F/A-18 Super Hornets and F-35 Lightnings catapulting off and landing on an aircraft carrier echoes that of the original film, for instance, as does Maverick’s introduction to his Top Gun students. But unlike the Star Wars prequels Lucas directed, Top Gun: Maverick actually does rhyme with its venerable predecessor even as it brings an iconic character forward in time.

Still, this sequel lacks a number of elements that made the original Top Gun so distinctive and memorable. Kosinski, for instance, is a fine filmmaker who expertly pulls together tense flight and action sequences that leave audiences biting their nails in suspense. But he lacks the verve and panache director Tony Scott brought to the original Top Gun, and the end result is a much more conventional action picture than its sleek and stylish predecessor.

Likewise, the soundtrack and score of Top Gun: Maverick don’t measure up to those of the original. The synthesizer-heavy score of composer Harold Faltermeyer has been replaced with a more traditional orchestral composition by modern movie music titan Hans Zimmer. The score certainly holds its own and incorporates key elements of Faltermeyer’s original, including the inimitable “Top Gun Anthem.” But as with Kosinski’s direction, Zimmer and collaborator Lorne Balfe take the score down a more conventional path.

Nor does the film incorporate its original soundtrack as effectively as Top Gun did back in 1986. Songs like “Danger Zone” and “Take My Breath Away” featured prominently throughout that movie, while others like “Mighty Wings” and “Playing with the Boys” helped bring dogfight sequences and the now-infamous volleyball scene to full life. Along with classic rhythm and blues tracks like “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” and especially “You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling,” Top Gun’s original soundtrack lent it a unique sonic palette that helps account for its enduring popularity.

By contrast, Top Gun: Maverick includes just two original songs on its soundtrack. The unremarkable band OneRepublic provides a forgettable backing track for the film’s beach football scrimmage scene, while pop queen Lady Gaga’s perfectly satisfactory power ballad “Hold My Hand” is relegated to barely audible background music early on before returning in full force for the end credits. Classic rock in the form of the Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again” punches up one of the movie’s first flight sequences, but otherwise the film’s soundtrack leaves little if any impression.

Top Gun: Maverick is also decidedly less sexy than its predecessor, perhaps due in part to the age of the lead actors involved - Cruise was in his mid-to-late 50s and Connelly in her late 40s when the movie was filmed before the COVID-19 pandemic. Where the original movie had a brief but steamy sex scene between Maverick and his love interest Charlie as well as constant references to oversexed fighter pilots, the sequel merely shows Maverick and Penny cuddling in bed after the fact. Similarly, Kosinski attempts to recapture the unintentionally homoerotic glory of Top Gun’s volleyball sequence with his beach football scrimmage, but the unsexy scrum that results can’t possibly live up to its inspiration no matter how hard the director tries.

But even if Top Gun: Maverick can’t quite reach its full potential as a movie and leaves some of its themes hanging as the credits roll, it’s a still an outstanding thrill ride from start to finish – and an eminently worthy successor to its iconic predecessor. It does not turn revered characters into utter failures or rely on nostalgia to do the necessary cinematic heavy lifting. The film instead chooses to bring Maverick into the present, wrestling with the existential questions that shadow an aging fighter pilot as he nears the end of his professional life.

In that, at least, Top Gun: Maverick succeeds so well that future attempts to revisit decades-old characters and stories will rightfully be judged by the high standard it has set.