The Dive - 4/1/23

Quote of the Month

"Fortune—deceptive in power's great blessings— you set in precarious, unstable positions the too-much exalted. Never do scepters possess tranquil peace or a day that is sure of itself. Anxiety after anxiety harries them, new storms always taxing their minds." - Seneca, Agamemnon, I.57-63

My Recent Writing:

What I’m Reading:

1. How China became a tech power—and how America can stay ahead

Why you should read it: In Foreign Affairs, technology analyst Dan Wang details how Chinese policy enabled Beijing to make leaps and strides in technology, and shows how America can keep it from overtaking the United States by investing as much in manufacturing as R&D.

“In a majority of manufactured goods, Chinese firms have moved beyond assembling foreign-made components to producing their own cutting-edge technologies. Along with its dominance of renewable power equipment, China is now at the forefront of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing. These successes challenge the notion that scientific leadership inevitably translates into industrial leadership. Despite relatively modest contributions to pathbreaking research and scientific innovation, China has leveraged its process knowledge—the capacity to scale up whole new industries—to outcompete the United States in a widening array of strategic technologies… For the United States and its allies, China’s arrival as a major tech power holds crucial lessons. Unlike the West, China has grounded its technology sector not in glamorous research and advanced science but in the less flashy task of improving manufacturing capabilities. If Washington is serious about competing with Beijing on technology, it will need to focus on far more than trailblazing science. It must also learn to harness its workforce the way China has, in order to bring innovations to scale and build products better and more efficiently. For the United States to regain its lead in emerging technologies, it will have to treat manufacturing as an integral part of technological advancement, not a mere sideshow to the more thrilling acts of invention and R & D.”

“The failure of the U.S. solar industry is part of a bigger story of decline in U.S. manufacturing. To a degree, this trend has been driven by increasing automation. But the sector is also beset by internal weaknesses. Consider the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like other countries, the United States needed vast quantities of personal protective equipment and other medical supplies. Yet U.S. firms struggled to adapt their production lines to make facemasks and cotton swabs— uncomplicated products by any measure—because they had lost much of the requisite process knowledge. By contrast, Chinese manufacturers were quickly able to retool for the emergency and produced many of the medical supplies that the United States and other countries needed… A big push by Apple to make more desktop computers in Texas, for example, floundered after 2012 because it lacked a supporting industrial ecosystem of component parts. One exception has been the United States’ rapid production of messenger RNA vaccines, which have proved more effective than China’s inactivated virus vaccines. To compete against China’s advanced industries in the years to come, however, the United States will need far more than a one-off biotech victory”

Why it matters: “…the United States has not yet come to grips with its own deficit in process knowledge. Certainly, Congress’s passage of the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 constitute major steps forward in industrial policy, given that both allocate billions of dollars of federal funding for advanced industries. But too much of U.S. policy—including this legislation—is focused on pushing forward the scientific frontier rather than on building the process knowledge and industrial ecosystems needed to bring products to market. As such, Washington’s approach to its growing tech rivalry with China risks repeating the mistakes it made in the solar industry, with U.S. scientists laying the foundation for a new technology only to see Chinese firms take the lead in building it… as an ideological starting point, a new industrial policy will need to be centered on workers and their process knowledge rather than on financial margins. Otherwise, it is likely to be China, not the United States, that leads the next technological revolution.”

2. Why America should get over its obsession with quick wars

Why you should read it: Rand Corporation analysts Raphael S. Cohen and Gian Gentile write in Foreign Policy that the American obsession with short, decisive wars runs counter to the country’s own historical experience and virtually all known records of armed conflict.

“Americans have long been fixated on the idea of the short, decisive war…A similar obsession with short wars colors the coverage of the Ukraine war today. In 2022, as it became clear Russia was about to invade Ukraine, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark Milley, the U.S. intelligence community, and most outside experts predicted a Russian victory in a matter of days. As the Russian advance sagged, a handful of commentators then predicted a speedy Ukrainian victory. Many more have judged the war unwinnable and called for a quick end through negotiations. The media, for its part, has labeled the war a stalemate during just about every lull in fighting… The number of truly quick wars in U.S. history have been few and far between. Most of these have been small affairs against second-tier powers, like the Reagan administration’s attack on Grenada or the George H.W. Bush administration’s intervention in Panama. In some cases, a short war proved more illusion than fact. The First Gulf War in 1990 lasted only 100 hours, but it gave way to three decades of direct U.S. military involvement in and over Iraq that continues to this day.”

“Over the years, the United States has tried any number of approaches to shorten its wars. Depending on the conflict, it has experimented with diplomacy and encouraged off-ramps to entrenched conflicts. When those have not worked, it has tried ‘shock and awe’ campaigns using overwhelming force to wow its adversaries into submission. Today, there are entire research programs at Washington think tanks focusing on ‘ending endless wars’—as if there were a lobby for engaging in such conflicts in the first place. In most cases, these efforts have failed: In recent decades, Washington’s wars have tended to last longer… No one can blame the near-universal desire to keep wars short. Still, as a matter of defense planning, the United States needs to assume that most of its wars will last a long time. Thankfully, wars are rare events. Most of the time, states only fight over what they perceive as irreconcilable issues of enough importance that they merit the investment of blood and treasure. If there were an easy solution, then most likely the war would have been avoided altogether. But precisely because states do not go to war on a whim also means they do not sue for peace on a whim, either."

Why it matters: “Obviously, no one wants to fight long, grueling wars. They are bloody and expensive. If war can be avoided in the first place, all the better. But if the United States must fight—for instance, over Taiwan—it should take a clear-eyed look at its own history and prepare for what will, in all likelihood, be a protracted conflict. It must ensure that it has the industrial capacity and manpower to sustain a long fight and the strategic vision to guide its efforts for the long haul… If the United States’ objective is to win, the only thing worse than fighting a long war may be thinking it’s possible to avoid one.”

3. How China recruits unwitting spies to steal America’s industrial secrets

Why you should read it: Using the case of an aerospace engineer named Hua, riter Yudhijit Bhattacharjee outlines how Chinese state intelligence services recruit unwary employees of American companies to carry out industrial espionage against the United States—and how American law enforcement struck back.

“In March 2017, an engineer at G.E. Aviation in Cincinnati whom I will refer to using part of his Chinese given name — Hua — received a request on LinkedIn… The LinkedIn request came from Chen Feng, a school official at the Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (N.U.A.A.), in eastern China. Like most people who use LinkedIn, Hua was accustomed to connecting with professionals on the site whom he didn’t know personally, so the request did not strike him as unusual. ‘I didn’t even think much about it before accepting,’ Hua told me. Days later, Chen sent him an email inviting him to N.U.A.A. to give a research presentation… Being recognized back home was especially fulfilling for Hua, who grew up poor in a small village and was the only child there from his generation to go to college. Beyond the prestige, the invitation also provided a free trip to China to see his friends and family. Hua arranged to arrive in May, so he could attend a nephew’s wedding and his college reunion at Harbin Institute of Technology. There was one problem, though: Hua knew that G.E. would deny permission to give the talk if he asked, which he was supposed to do. ‘Since G.E. is a high-tech company, it is difficult to get approval even to present at conferences in the United States,’ he says. The company was concerned about giving away proprietary information.”

“Like China’s economy, the spying carried out on its behalf is directed by the Chinese state. The Ministry of State Security, or M.S.S., which is responsible for gathering foreign intelligence, is tasked with collecting information in technologies that the Chinese government wants to build up. The current focus, according to U.S. counterintelligence experts, aligns with the ‘Made in China 2025’ initiative announced in 2015. This industrial plan seeks to make China the world’s top manufacturer in 10 areas, including robotics, artificial intelligence, new synthetic materials and aerospace. In the words of one former U.S. national security official, the plan is a “‘road map for theft…’ Perhaps most unsettling is the way China has sought to exploit the huge numbers of people of Chinese origin who have settled in the West. The Ministry of State Security, along with other Chinese government-backed organizations, spends considerable effort recruiting spies from this diaspora. Chinese students and faculty members at American universities are a major target, as are employees at American corporations. The Chinese leadership ‘made the declaration early on that all Chinese belong to China, no matter what country they were born or living’ in, James Gaylord, a retired counterintelligence agent with the F.B.I., told me. ‘They started making appeals to Chinese Americans saying there’s no conflict between you being American and sharing information with us. We’re not a threat. We just want to be able to compete and make the Chinese people proud. You’re Chinese, and therefore you must want to see the Chinese nation prosper…’ An even more troubling consequence of China’s exploitation of people it regards as Chinese is that it can lead to the undue scrutiny of employees in American industry and academia, subjecting them to unfair suspicions of disloyalty toward the United States.”

Why it matters: “Hua didn’t regard his visit to China to share his technical expertise as extraordinary in any way. Many scientists and engineers of Chinese origin in the United States are invited to China to give presentations about their fields. Hua couldn’t have known that his trip to Nanjing would prove to be the start of a series of events that would end up giving the U.S. government an unprecedented look inside China’s widespread and tireless campaign of economic espionage targeting the United States, culminating in the first-ever conviction of a Chinese intelligence official on American soil…the evidence laid out during Xu’s trial goes far beyond merely proving his guilt — it uncovers the systematic nature of China’s vast economic espionage. The revelation of [MSS agent] Xu [Yanjun]’s activities lifts the veil on how pervasive China’s economic espionage is, according to the F.B.I. agent. If just one provincial officer can do what he did, the agent suggests, you can imagine how big the country’s overall operations must be.”

4. Why Ukraine ought to force a rethink of notions of a “reasonable prospect of success” in just war theory

Why you should read it: Stanford researcher Rhiannon Neilson argues in Lawfare that notions of a reasonable prospect of success—a key criterion under both traditional and revisionist views of just war theory—may be fundamentally flawed and need to be reconsidered given the course of events in Ukraine.

“…as the tanks first rolled across the border a year ago, Ukraine’s likelihood of defeating Russian aggression was considered remote. Most analysts expected a swift Russian take-over, seemingly doubting the smaller state’s willingness to fight, let alone triumph. Russia’s military ostensibly dwarfed Ukraine’s. Kyiv was forecast by experts to fall within the week. Two days after the invasion, world leaders urged Zelenskyy to leave and offered him a way out—to which he famously retorted, ‘I need ammunition, not a ride.’ In other words, in the very early days, Ukraine did not seem to have a foreseeable prospect of success—or, to put it plainly, a reasonable chance of winning the war… According to the prevailing moral precept by which wars are judged, the just war tradition, Ukraine would not have satisfied all jus ad bellum criteria at the start of Russia’s invasion. To permissibly resort to war, jus ad bellum requires states to have a ‘just cause’ (such as self-defense), possess a ‘legitimate authority,’ ensure war is a ‘last resort’ and necessary, satisfy ‘proportionality,’ be motivated by a ‘right intention’ and have a ‘reasonable prospect of success.’ This last criterion is understood as a reasonable chance of victory. This seems intuitively coherent enough: Why put soldiers (on both sides) and civilians through needless suffering and bloodshed if there is no sound chance of winning? According to just war revisionists, even if the war is one of self-defense (as is the case with Ukraine), if it is unlikely to succeed, pursuing such war is morally prohibited. The satisfaction of the ‘success’ criterion, for revisionists, is necessary for going to war. Just war traditionalists, however, regard the success criterion as prudential: It is not required, but it should ‘be taken into account in the decisions of statecraft.’ For the traditionalists, self-defense could, in other words, overrule the need to have a decent chance of winning… Because many analysts regarded Ukraine’s chances of success—of entirely beating Russia—as minimal, revisionists would have ostensibly considered the resort to a war of self-defense unjust.”

“The war in Ukraine mounts a challenge to just war thinking, especially for revisionists but also for traditionalists. Specifically, the war highlights the urgent need to revise the success criterion beyond the logic of winning versus losing (particularly if it is a necessary condition in jus ad bellum, as per the revisionists). More forcefully, the war in Ukraine prompts a possible rejection of the success criterion altogether. In some ways, this view seems to echo the traditionalist approach; that is, success is a tertiary consideration and can be set aside should there be a strong enough just cause, as in Ukraine. But if, according to traditionalists, success can be so quickly ignored upon satisfying a just cause, then why include it in jus ad bellum in the first instance? Its inclusion in just war calculations is seemingly neither necessary (as per the revisionists) nor prudential (as per the traditionalists). Such lessons from Ukraine have profound implications for political leaders deciding whether to wage war… As one year of fighting in Ukraine demonstrates, there are many factors that can sway the odds in the defending party’s favor as the war unfolds. As such, must there be a requirement to give even nominal consideration to foreseeable success prior to taking up arms? Both revisionists and traditionalists might do well to simply set aside such a condition altogether."

Why it matters: “The war in Ukraine brings to the fore the grim reality of just war revisionists demanding victims of unjust aggression not to fight if there is no reasonable prospect of success—or, more concretely, victory. To revisionists, failing the success condition means that it is not only morally repugnant but morally wrong to fight to defend one’s homeland. There seems to be something deeply troubling with this logic… it is unclear whether political and military decision-makers ought to give any credence to the success criterion when deciding to wage war. Success, to traditionalists, is a supplemental consideration, especially in the case of self-defense, like in Ukraine. The criterion seems simply to serve as a question for victims to consider when deciding whether to defend themselves: ‘Your chances are slim, so are you sure?’ The response does not appear to impact the moral permissibility of the war. The conflict in Ukraine thus prompts a possible rejection of ‘success’ from jus ad bellum entirely—both as a necessary (per revisionists) and prudential (per traditionalists) criterion.”

5. Why the era of the Silicon Valley “moonshot” has ended

Why you should read it: Washington Post reporters Gerrit De Vynck, Caroline O’Donovan, and Naomi Nix observe that between cost-cutting and a rash of layoffs the era of speculative projects appears to be coming to an end in Silicon Valley.

“Eight years ago, Google’s founders split the company up into separate entities and named the collection Alphabet. The idea was to separate the core business — the company’s giant advertising machine that made it one of the most powerful corporations in the world — from the side projects that needed time to develop but could one day become Google’s next big moneymaker… But that next big moneymaker hasn’t materialized. Revenue still comes overwhelmingly from advertising. Google has shuttered most of its so-called ‘moonshots’ — from internet-delivering balloons to glucose-measuring contact lenses.”

“As the decade-long bull market came stuttering to an end and tech stock prices fell throughout last year, pressure to cut costs from Wall Street built and in the past few months a deluge of layoffs and cost-cutting has flooded Silicon Valley. The big-idea side projects that were supposed to become the revenue-drivers of the future have been particularly hard hit, with some of them being completely dismantled, and others facing deep cuts… Higher interest rates means the investment needed to keep spending on money-losing projects is getting harder to find… Giving up the moonshot dream marks another stage in the companies’ march into middle age. Google, Facebook and Amazon all grew rapidly from start-ups to tech giants through the first two decades of the millennium by upsetting the balance forged by companies that came before them… The biggest tech companies have indeed managed to stave off disrupters. But it wasn’t always through reinventing themselves with internally created big ideas. Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook made hundreds of acquisitions over the past two decades, buying both sizable up-and-coming competitors and tiny start-ups. Google’s Android operating system, Facebook’s mobile advertising business and Amazon’s audiobooks empire all initially came through acquisition.”

Why it matters: “A similar dynamic has been playing out over the past year when it comes to new generative artificial intelligence tools that can produce text, images, sounds and videos that look and feel like they were created by humans. Start-ups like OpenAI and Stability AI pushed their products out to the public, capturing a wave of marketing attention and wonder at the new tools, even though much of the technology was based on ideas developed earlier by the Big Tech companies… The shift is a major change for the tech industry’s culture, where employees would jump from well-paying jobs at Big Tech companies to risky start-ups, comfortable in the assumption that they could return if the smaller company didn’t work out.”

6. Why GPT-4 doesn’t really understand what you’re saying

Why you should read it: In a Q&A for Nautilus, Santa Fe Institute President David Krakauer contends that large language models like GPT-4 doesn’t have the sophistication or capability to match human reasoning about the world.

“There’s a kind of understanding which is just coordination. For example, I could say, ‘Can you pass me the spoon?’ And you’d say, ‘Here it is.’ And I say, ‘Well, you understood me!’ Because we coordinated. That’s not the same as generative or constructive understanding, where I say to you, ‘I’m going to teach you some calculus, and you get to use that knowledge on a problem that I haven’t yet told you about…’ understanding, like information, has several meanings—more or less demanding. Do these language models coordinate on a shared meaning with us? Yes. Do they understand in this constructive sense? Probably not.”

“I’d make a big distinction between super-functional and intelligent. Let me use the following analogy: No one would say that a car runs faster than a human. They would say that a car can move faster on an even surface than a human. So it can complete a function more effectively, but it’s not running faster than a human. One of the questions here is whether we’re using ‘intelligence’ in a consistent fashion. I don’t think we are… Another dimension of difference, which is very important, is that our cognitive apparatus evolved. The environment that created the attributes that we describe as intelligence and understanding is very rich. Now look at these algorithms. What is their selective context? Us. We are cultural selection on algorithms. They don’t have to survive in the world. They have to survive by convincing us they’re interesting to read. That evolutionary process that’s taken place in the training of the algorithm is so radically different from what it means to survive in the physical world—and that’s another clue. In order to reach even remotely plausible levels of human competence, the training set that these algorithms have been presented with exceed what any human being in a nearly-infinite number of lifetimes would ever experience. So we know we can’t be doing the same thing. It’s just not possible.”

Why it matters: “If I said to you, ‘There’s a trolley rolling down the hill, and there’s a cat in its path. What happens next?’ You’re not just trying to estimate the next word, like GPT-4. You’re forming in your mind’s eye a little mental, physical model of that reality. And you’re going to turn around to me and say, ‘Well, is it a smooth surface? Is there lots of friction? What kind of wheels does it have?’ Your language sits on top of a physics model. That’s how you reason through that narrative. This thing does not. It doesn’t have a physics model… You could say to it, “What physics model is behind the decision you’re now making?” And it would now confabulate. So the narrative that says we’ve rediscovered human reasoning is so misguided in so many ways. Just demonstrably false. That can’t be the way to go.”

7. How Russia bungled its invasion of Ukraine through overreliance on unconventional warfare

Why you should read it: Royal United Services Institute scholars Jack Watling, Oleksandr V Danylyuk, and Nick Reynolds explain how Moscow’s overreliance on unconventional warfare and intelligence operations led to its early failures during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“The lack of proper logistics, the lack of fuel and ammunition, the vulnerability of long Russian convoys, poorly protected even from air raids, all indicate that Russia carried out the invasion as a military demonstration, without seriously considering the need to conduct full-fledged long-term combat operations. To a large extent, the small group of planners thought to repeat the success of the Crimean operation of 2014, which also made no sense from a military point of view and was planned based on the absence of military resistance from Ukraine… Despite the extent of Russia’s efforts – only a fraction of which are outlined above – it is noteworthy that Russia failed to bring about the destabilisation its plan called for. Even with the presence of powerful agents in state authorities, as well as prepared structures that could be involved in internal destabilisation, Russia has not managed to foment an internal political crisis in Ukraine. First, it was not possible to achieve the main prerequisites for full-scale protests. Despite pressure and influence, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy did not agree to renounce Ukraine’s bid for membership of NATO and make other concessions to Russia unacceptable to the majority of Ukrainians. Second, as part of intelligence sharing, Western intelligence services transmitted to Ukraine not only information about Russia’s preparations for a military invasion, but also about Russian intentions to destabilise Ukraine internally, as well as about persons who directly participated in it. Public release of information about such intentions was also an important element of neutralising Russian efforts.”

“The Russians mistakenly appear to have projected on to Ukraine the same top- down command culture of their own forces. A large portion of the middle echelon of officials that were Russian agents simply stopped responding to messages early in the invasion or else abandoned their posts, severing chains of command from the central government to tactical units… Russia’s agents tried to convince local commanders and officials not to resist. They did not do this by presenting themselves as speaking on behalf of the Russians, but instead cited the local disparity in forces and the desire to save Ukrainian lives. The aim was to slow down a decision to resist for long enough to allow Russian forces to occupy key strategic centres. Resistance in this framework would be sporadic and isolated. In this context, the model for the wider Russian invasion plan may be observed in southern Ukraine – where it proved much more successful. Furthermore, since the task of Russia’s agents was to isolate Ukrainian units through obstruction and encourage junior paralysis and surrender, many of them withdrew their work from the government rather than actively operating to participate in the occupation. The intent was that they would emerge once the territory was occupied, rather than engage in some sort of coup or direct action before occupation was achieved… The whole logic of the employment of forces was premised on the success of Russia’s unconventional operations and yet, as already discussed, the preconditions for that success in terms of the political destabilisation of Ukraine had not yet been achieved. There remains an unanswered question as to why the Russian leadership decided to begin the invasion without establishing the required preconditions. This may be understood as a strategic error of judgement by Putin personally… The Russians were so confident that they would succeed in hours that their support apparatus had rented apartments around the key sites from which their special forces were supposed to operate in Kyiv.”

Why it matters: “…it is evident that the Russian special services managed to recruit a large agent network in Ukraine prior to the invasion and that much of the support apparatus has remained viable after the invasion, providing a steady stream of human intelligence to Russian forces. The internal threat significantly constrained the political room for manoeuvre for the Ukrainian state prior to the conflict and this produced unfavourable conditions for preparing the population for war. There has, for many years, been a bias in many states to favour collection against Russian activities on their territories. The evidence from Ukraine strongly suggests that Russian subversion should be actively resisted and disrupted before it can build up the mutually supporting structure that existed in Ukraine… However, there are also clearly considerable deficiencies in Russia’s approach to unconventional warfare. At a fundamental level the Russian special services lack self-awareness, or at least the honesty to report accurately about their own efforts. In the case of Ukraine, a plan was attempted that was critically dependent on unconventional methods when the preconditions for success had not yet been achieved. This reveals wider cultural problems in the Russian services. That they are directed to bring about an outcome without independently assessing the viability of the plan creates a reporting culture where officers are encouraged to have a significant optimism bias. Furthermore, there appears to be a systemic problem of overreporting one’s successes and concealing weaknesses to superiors…The upshot is that, while the Russian services may have failed in Ukraine, this is unlikely to prevent their being central to the coercive activities of the Russian state in the future, and countering them will remain no less important.”

8. How China lost central and eastern Europe

Why you should read it: In Foreign Policy, Romanian think-tanker Andreea Brinza says that China’s once-promising diplomatic fortunes in central and eastern Europe took a turn for the worse due to Beijing’s propensity to go all-in on relationships with specific individual politicians in power at particular times.

“In the 2010s, many countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) were competing to become ‘China’s gateway to Europe.’ Fast-forward to today, and nobody is trying to win that title. China lost the CEE region—not only because Beijing didn’t know how to properly manage its relations with the countries from the region, but, most important, because it built those relations largely on the backs of the leaders in power… For a long period, China’s strategy toward the CEE was to build very close ties with those politicians who had already shown a pro-Chinese stance. This approach had its zenith in the 2010s, soon after the establishment of a regional forum for cooperation with China, the 16+1 mechanism. But it also drew China into internal political debates in a region in which negative memories of communism are still raw and controversial. Now, the political landscape has changed to China’s disadvantage, and the recent election of Petr Pavel as the president of the Czech Republic is the latest shift in this direction.”

“The same pattern has repeated in countries such as Romania and Greece. In Bucharest, Victor Ponta’s tenure as prime minister (2012-2015) saw Romania-China relations experiencing their best moment since the fall of communism, as was the relationship between China and Ponta himself. According to a source familiar with the matter, Ponta encouraged strong but less institutionalized relations between his administration and China, sometimes circumventing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs…Once Ponta left, relations with China slowly started to deteriorate, only encountering a brief hiatus when another left-wing prime minister, Viorica Dancila, came to power. In the meantime, all the deals promoted in 2013 were abandoned, and after the emergence of tensions between the United States and China and then the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China largely found the door to high-level Romanian politics shut… In the Czech Republic, like in Romania or Greece, China focused too much on relations with the leader in power and didn’t invest enough in diversifying its elite ties or public support. On the contrary, in the former communist countries of the CEE, it failed to understand that vast swaths of the population—and the political parties that represented them—would become critical of China if it was seen as too close to leaders with images tainted by populism, authoritarianism, or corruption.”

Why it matters: “In other regions of the world, China has been more successful, either by maintaining strong ties to authoritarian governments or by reaching out more broadly among political elites or establishing economic links that can withstand a change of government. But Beijing’s lack of interest in engaging with countries as a whole, in building institutional relations, and in courting public opinion in the CEE region suggests that China lacks a real understanding of how a democracy works and how to build long-lasting ties that go beyond a few China-friendly politicians. It also shows that instead of thinking long term, Beijing prefers easier short-term solutions, in the form of a few politicians it can trust who don’t take much hassle to attract.”

9. How inept regulations keep America from developing supersonic commercial aviation

Why you should read it: Substacker and economist Eli Dourado lays out the background of the convoluted regulations that need to be changed if the United States is ever to have a commercially viable supersonic air transport.

"Fifty years ago today, on March 23, 1973, Alexander P. Butterfield, the Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration, issued a rule that remains one of the most destructive acts of industrial vandalism in history… The rule imposed a speed limit on US airspace. Not a noise standard, which would make sense. A speed limit.”

“This speed limit has naturally distorted the development of civil aircraft. For fifty years, the aviation industry has worked to improve subsonic aviation. Commercial passenger aircraft are safer and more economical today than they were in 1973, but they are no faster… If we had propagated the rate of growth in commercial transatlantic aircraft speeds that existed from 1939 to the mid-1970s, we would have Mach-4 airliners by now. But the overland ban put an end to all that. It made small supersonic aircraft, which need to fly shorter overland routes, essentially illegal, closing off the iteration cycle that could drive progress in the industry… So let’s say that NASA has robust data from X-59 [quiet supersonic test aircraft] on human response to sonic boom, more robust than what we have managed to collect over the last 70 years. They bring it to ICAO, specifically CAEP’s Working Group 1, which devises noise standards, in around 2025 or 2026… Before the FAA can formally adopt the new ICAO standard, it will need to do an Environmental Impact Statement under NEPA. EISs can be challenging in any circumstance, but for supersonics it will be especially hard because aviation will be one of the last sectors to decarbonize. Even if companies are using synthetic, net-zero fuel, the aircraft will still be burning liquid hydrocarbons, which raises emissions relative to creating synthetic fuels and, say, storing them underground. Environmental groups will inevitably sue, potentially delaying the standard beyond the EIS preparation time… If we’re lucky, we’ll have a sonic boom standard implemented in the United States by the late 2030s.”

Why it matters: “I’m struck by the fact that American economic growth went off the rails in 1973, the same year the overland ban on supersonic flight came into force. The speed limit cannot be responsible for the entirety of the Great Stagnation, of course… Yet, the ban is not unrelated to economic stagnation. To borrow a term from Ross Douthat, there is something decadent about putting a complete halt to the development of a key technology simply because a few otherwise harmless sonic booms might annoy a vocal minority. With boom-shaping technology we know is possible, a tiny vocal minority. The cultural forces that led to and sustain the ban have certainly halted other progress.”

Odds and Ends

Attorney General Merrick Garland, die-hard Swiftie…

How Minnesota’s Iron Range helped the United States win World War II…

Why Duluth, Minnesota has seen its population grow thanks to climate change…

When were wine grapes first domesticated? At least 11,000 years ago, scientists now believe…

How Zen-slacker archetype Keanu Reeves became Hollywood’s biggest action star…

What I’m Listening To

Lady Gaga’s spartan live performance of Top Gun: Maverick’s “Hold My Hand” at the 2023 Oscars.

“All Of The Girls You Loved Before,” a previously unreleased song from Taylor Swift’s Lover sessions in 2019.

Lola Collette’s cover of the Martha and the Vandellas classic “Nowhere To Run” from the John Wick: Chapter 4 soundtrack.

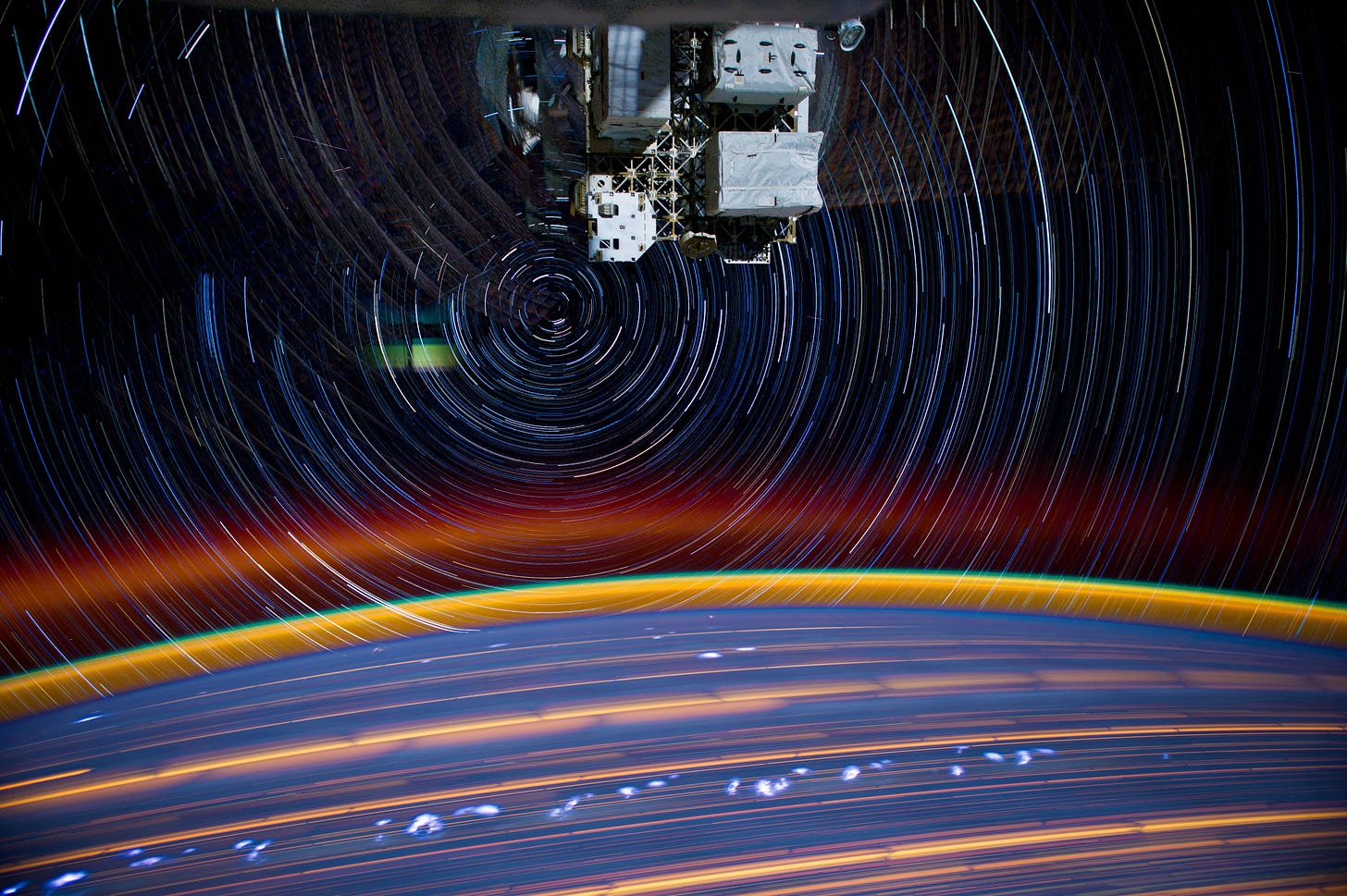

Image of the Month